Mynydd Parys

The term ‘mountain’ (mynydd in Welsh) is more of a title rather than a descriptor; “Hills of any size are scarce in Anglesey, but the dignity of the term ‘mountain’ is conferred on only a select few” (E.R.W. 1914: 172). It is also an ancient attribution. Parys Mountain’s original name was Mynydd Trysglwyn. Like many Welsh place names, Mynydd Trysglwyn is likely a description of the area and has been translated to the "hillside covered in a thick grove of rough trees covered with scaly lichen growth" (PUG 2020). At the start of the 13th century, the mountain's name was changed to Parys Mountain to reflect the area’s ownership by the politician Robert Parys (PUG 2020).

One of the sections I found most interesting at Parys Mountain was the exposed rock face on the northern ridge of the Great Opencast. It exposed a very obvious geographical stratigraphy in a veritable rainbow of colours. While I cannot determine the composition of each layer and when it was deposited, the slant of the stratigraphy is indicative of a period of uplift. This occurred during a period of volcanic activity at the start of the Silurian (443.8 million years ago).

The geology of Parys Mountain can best be summarised as “a folded and faulted sequence of Ordovician volcanic and sedimentary rocks and Silurian sedimentary rocks” (Westhead 1991: 132). During the Ordovician (485.4 – 443.8 million years ago), the Parys Mountain locality was a basinal marine environment, as evidenced by marine shale deposits (Westhead 1991, Barrett et al. 2001). Volcanic activity began at the start of the Silurian, caused by intraplate rifting (Barrett et al. 2001), depositing massive sulfides hosted within rhyolite across the site (Westhead 1991, Barrett et al. 2001). Another layer of shale lies above these volcanic deposits, indicating that the volcanism also occurred in a submarine environment (Barrett et al. 2001). Additionally, there is evidence of hydrothermal activity after the period of volcanicity, which deposited sulfides within the surrounding shales (Barrett et al. 2001).

K. Royce 2020 - CC BY-SA 4.0

Parys Mountain has been mined since the Early Bronze Age, both at the surface and deep underground (Ixer & Budd 1998, Timberlake 2017, Timberlake & Marshall 2018). Prehistoric miners accessed pyrite and chalocopyrite-bearing quartz veins with the Odivician shale (Ixer & Budd 1998) via steep opencasts over 20m deep (Timberlake & Marshall 2018) and shafts up to 50m deep (Timberlake 2017). Hammerstone tools and fire-setting were used to extract the ore from the surrounding rock (Ixer & Budd 1998, Timberlake 2017, Timberlake & Marshall 2018), which produced an estimated 2-4 tons of metal during this period (Timberlake 2017). The site was abandoned between 1600-1500 BCE, possibly due to flooding (Timberlake & Marshall 2018), and remained in disuse for centuries. Mining briefly resumed during the Roman period, but it was not until the mid-18th century that any large-scale mining operations occurred (North 1927).

On March 2nd, 1768, Rowland Pugh found “the Great Lode” (Carradice 2012) of chalcopyrite-rich ore within the Lower Silurian shale (Barret et al. 2001). This ore was in great quantity and close to the surface, allowing for easy extraction (Carradice 2012). People flocked to the area to work the mine, and the once sleepy town of Amlwch quickly became a bustling port that could keep up with volume of ore being shipped around the world. So much copper ore was being extracted that it dominated the global market, and Parys Mine quickly became one of the largest and most important mines across Europe (North 1927, Carradice 2012). The rapid increase in the copper supply however significantly reduced the price of the metal, which in turn negatively affected many smaller, less productive mines, such as those in Cornwall, England (North 1927).

Yet, these easily accessible deposits quickly ran out around the turn of the 19th century (Carradice 2012). Miners were forced to dig deeper, but none of the veins found could produce as much as “the Great Lode”. Production dwindled over the century, but mining continued until the turn of the 20th century.

Exploratory mining at Parys Mountain began in the 1960s (Anglesey Mining plc 2020). Various shafts were drilled in search for deep ore deposits. In 1990, a feasibility study was performed to determine whether sufficient ore was present to resume mining operations. While the results were favourable, the economy was not (Anglesey Mining plc 2020), postponing production indefinitely.

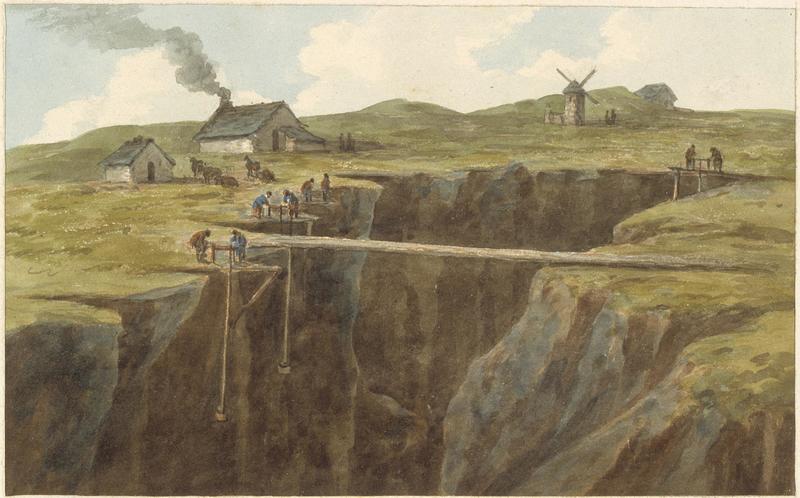

Copper mines on the Parys Mountain by John Warwick Smith - painted in 1790

© Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales - Item # NMW A 3199

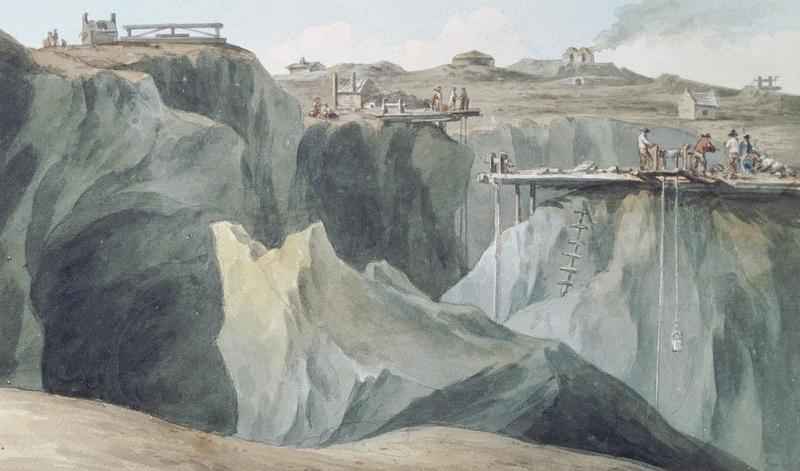

Junction of Mona and Parys Mountain Copper Mines by John Warwick Smith - painted in 1789

© Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales - Item #NMW A 3198

The industrial-scale mining at Parys Mountain has had an immense negative environmental effect on the surrounding area. Afon Goch (Red River in Welsh) is formed from the rainwater that accumulates at Parys Mine (Scott et al. 2014). The water reacts with sulfides, such as pyrite, to form acidic products that can dissolve surrounding material, increase acidity and allow for other toxic compounds to enter the waterway. This process is known as acid mine drainage. The ecotoxic river then flows through Amlwch to the Irish Sea where it deposits vast quantities of toxic elements, such as copper, zinc, arsenic, and cadmium (Scott et al. 2014).

As a result of the acidity and toxicity, very little lives in and around Parys Mountain and Afon Goch. However, many sectors are making the most of the situation. Researchers are studying the unique species of extremophiles that have been identified in the acidic waters and the plant life that is slowly returning to the mountain side. Archaeologist continue to excavate areas of the mountain to better understand how the site was used during the Bronze Age. Parys Mountain is also the type locality for the mineral anglesite (PbSO4) and is likely host to other rare minerals. And films crews have made use of the extraterrestrial-like landscape as a location for a number of tv shows and films (BBC News Wales 2003, Anglesey Mining plc 2020).

English Text:

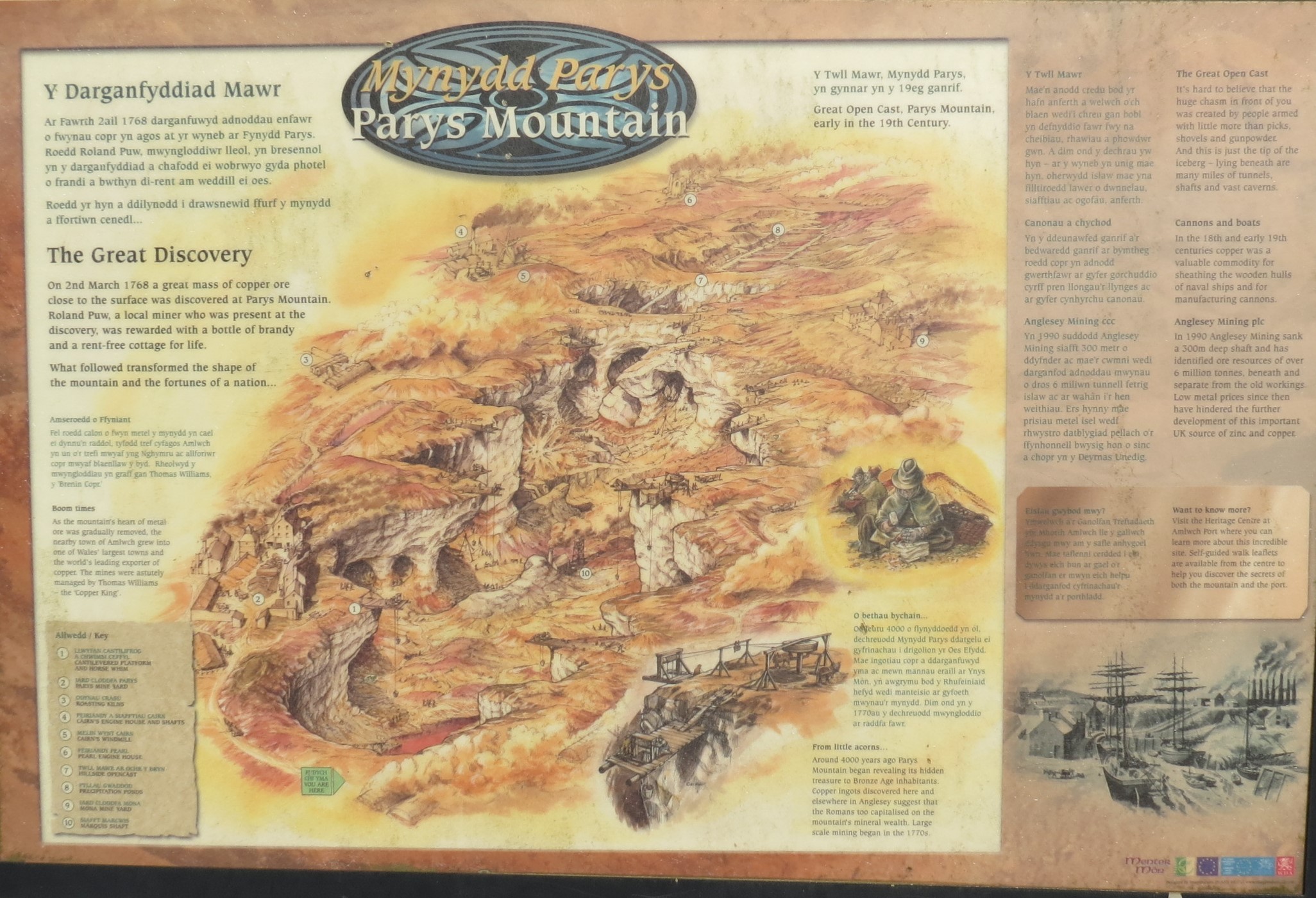

The Great Discovery

On 2nd March 1768 a great mass of copper ore close to the surface was discovered at Parys Mountain. Roland Puw, a local miner who was present at the discovery, was rewarded with a bottle of brandy and a rent-free cottage for life.

What followed transformed the shape of the mountain and the fortunes of a nation...

Boom Times

As the mountain's heart of metal ore was gradually removed, the nearby town of Amlwch grew into one of Wales' largest towns and the world's leading exporter of copper. The mines were astutely managed by Thomas Williams - 'the Copper King'.

From little acorns...

Around 4000 years ago Parys Mountain began revealing its hidden treasure to Bronze Age inhabitants. Copper ingots discovered here and elsewhere in Anglesey suggest that the Romans too captialised on the mountain's mineal wealth. Large scale mining began in the 1770's.

The Great Opencast

It's hard to believe that the huge chasm in front of you was created by people armed with little more than picks, shovels and gunpowder. And this is just the tip of the iceberg - lying beneath are many miles of tunnels, shafts and vast caverns.

Cannons and Boats

In the 18th and 19th centuries copper was a valuable commodity for sheathing the wooden hulls of naval ships and for manufacturing cannons.

Anglesey Mining plc

In 1990 Anglesey Mining sank a 300m deep shaft and has identified ore resources of over 6 million tonnes, beneath and separate from the old workings. Low metal prices since then have hindered the further development of the important UK sources of zinc and copper.

English Text:

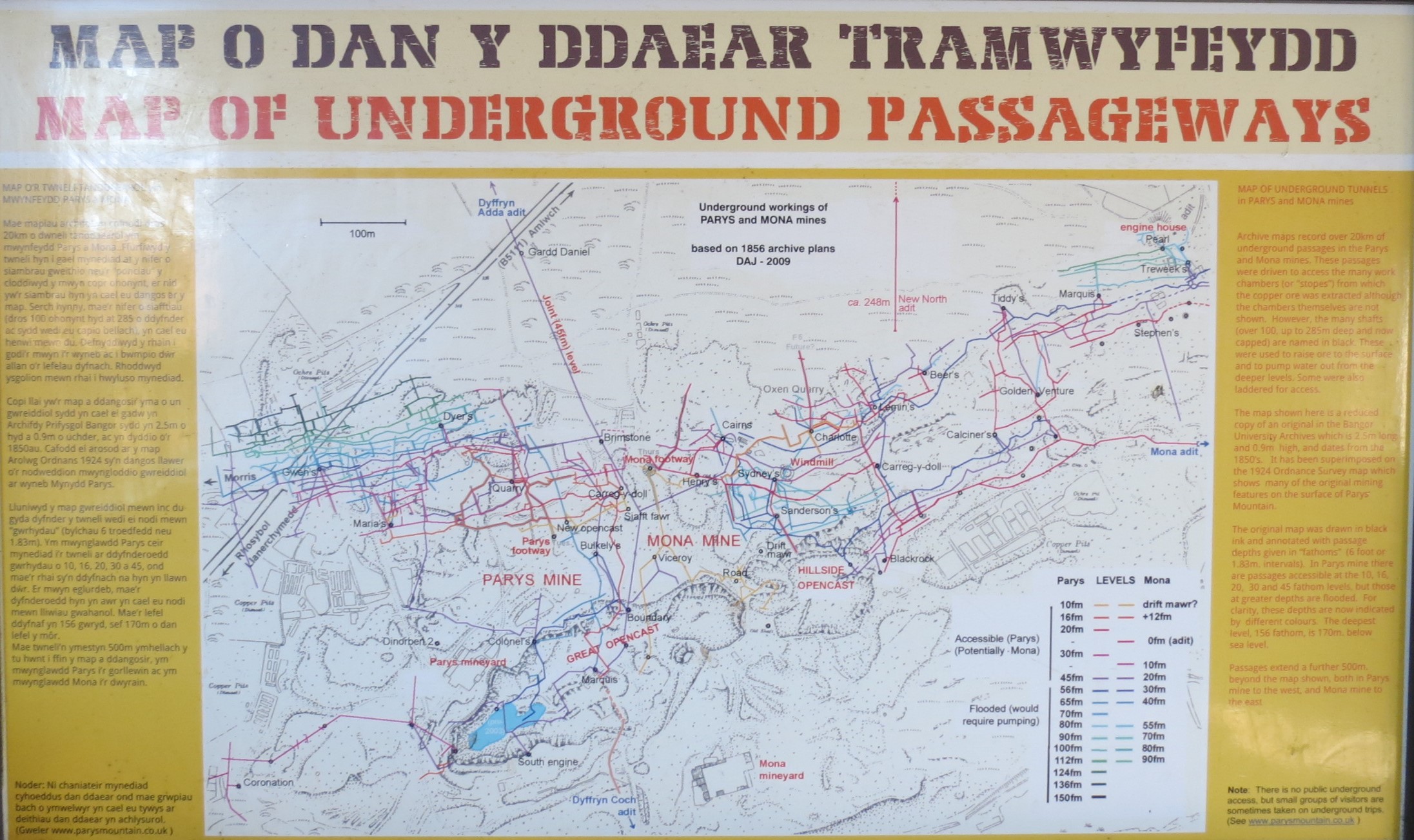

Archive maps record over 20km of underground passages in the Parys and Mona mines. These passages were driven to access the many work chambers (or 'stopes') from which the copper ore was extracted, although the chambers themselves are not shown. However, the many shafts (over 100, up to 285m deep and now capped) are named in black. These were used to raise ore to the surface and to pump water out from the deeper levels. Some were also laddered for access.

The map shown here is a reduced copy of an original in the Bangor University Archives which is 2.5m long and 0.9m high, and dates from the 1850's. It has been superimposed on the 1924 Ordinance Survey map which shows many of the original mining features on the surface of Parys Mountain.

The original map was drawn in black ink and annotated with passage depths given in 'fathoms' (6 foot or 1.83m intervals). In Parys mine there are passages accessible at the 10, 16, 20, 30, and 45 fathom levels, but those at greater depths are flooded. For clarity, these depths are now indicated by different colours. The deepest level, 156 fathom, is 170m below sea level.

Passages extend a further 500m beyond the map shown, both in Parys mine to the west, and Mona mine to the east.

English Text:

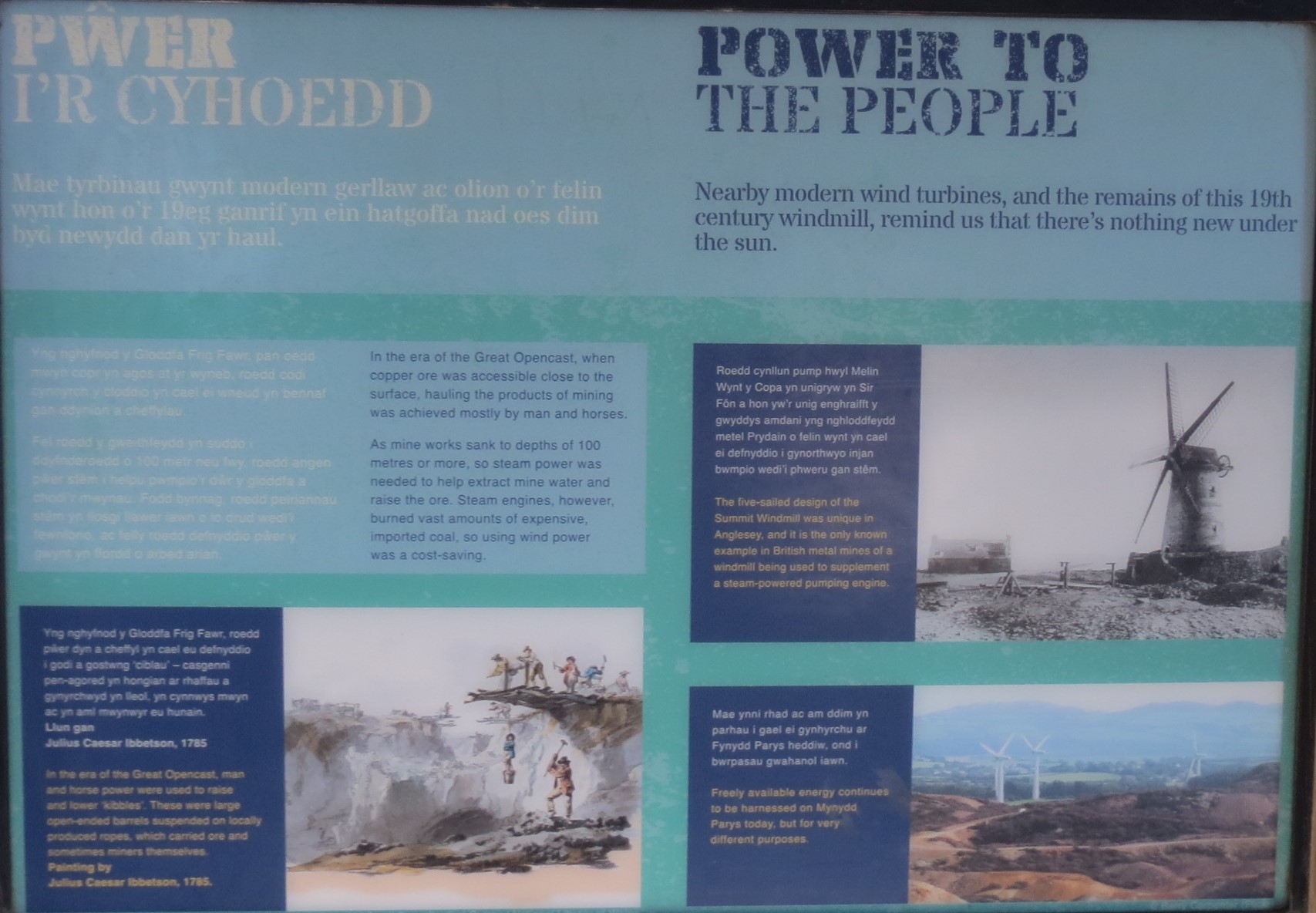

Nearby modern wind turbines, and the remains of this 19th century windmill, remind us that there's nothing new under the sun.

In the era of the Great Opencast, when copper ore was accessible close to the surface, hauling the products of mining was achieved mostly by man and horses.

As mine works sank to depths of 100 metres or more, so steam power was needed to help extract mine water and raise the ore. Steam engines, however, burned vast amounts of expensive, imported coal, so using wind power was a cost-saving.

English Image Captions:

In the era of the Great Opencast, man and horse power were used to raise and lower 'kibbles'. These were large open-ended barrels suspended on locally produced ropes, which carried ore and sometimes miners themselves. Painting by Julius Caesar Ibbetson, 1785

The five-sailed design of the Summit Windmill was unique in Anglesey, and it is the only known example in British metal mines of a windmill being used to supplement a steam-powered pumping engine.

Freely available energy continues to be harnessed on Mynydd Parys today, but for very different purposes.

English Text:

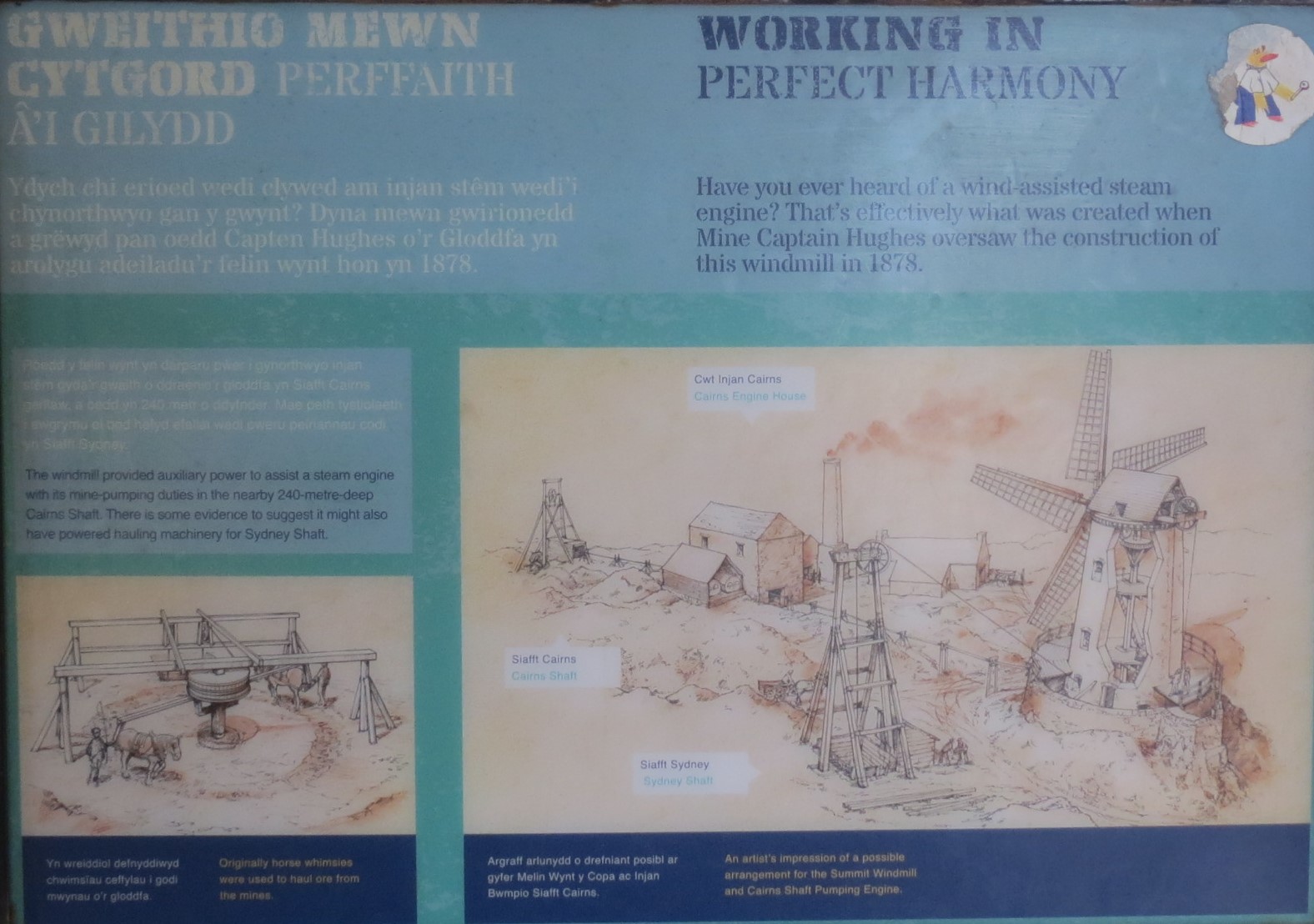

Have you ever heard of a wind-assisted steam engine? That's effectively what was created when Mine Captian Hughes oversaw the construction of this windmill in 1878.

The windmill provided auxiliary power to assisr a steam engine with its mine-pumpung duties in the nearby 240-metre-deep Cairns Shaft. There is some evidence to suggest it might also have powered hauling machinery for Sydney Shaft.

English Image Captions:

Originally horse whimsies were used to haul ore from the mines

An artist's impression of a possible arrangement for the Summit Windmill and Cairns Shaft Pumping Engine

- Anglesey Mining plc. 2020. Parys Mountain Mine - historical outline. Available at: http://www.angleseymining.co.uk/Parys-Mountain-Mine-Historical-Outline. [Accessed 27 October 2020]

- Barrett, T. 2001. Volcanic Sequence and Alteration at the Parys Mountain Volcanic-Hosted Massive Sulfide Deposit, Wales, United Kingdom: Applications of Immobile Element Lithogeochemistry. Economic Geology, 96, 1279-1305. 10.2113/96.5.1279.

- BBC News Wales. 2003. Acid water drained from mine. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/2922535.stm. [Accessed 27 October 2020].

- Carradice, P. 2012. Copper kingdom at Parys Mountain. BBC Wales History. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/waleshistory/2012/02/copper_kingdom_parys_mountain_amlwch.html. [Accessed 27 October 2020].

- Grwp Tanddaearol PARYS Underground Group (PUG). 2020. General history of Parys and Mona copper mines. Available at: http://parysmountain.co.uk/history/. [Accessed 27 October 2020].

-

Ixer, R. and Budd, P. 1998. The Mineralogy of Bronze Age Copper Ores from the British Isles: Implications for the Composition of Early Metalwork. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 17: 15-41. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00049

-

North, F.J. 1927. The Natural Resources of Wales. The Welsh Oulook, 14, 12 321-324.

-

Scott, C., Mayes, W. and Redman, V. 2014. Mynydd Parys & Afon Goch. Environmental Resistance Press: UK.

-

Timberlake, S. 2017. New ideas on the exploitation of copper, tin, gold, and lead ores in Bronze Age Britain: The mining, smelting, and movement of metal. Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 32: 7-8, 709-727, DOI: 10.1080/10426914.2016.1221113

-

Timberlake, Simon & Marshall, Peter. 2018. Copper mining and smelting in the British Bronze Age: new evidence of mine sites including some re-analysis of dates and ore sources. In E. Ben-Yosef (ed.) Mining for Ancient Copper Essays in Memory of Beno Rothenberg. Eisenbrauns: Winona Lake. 418–434.

-

W., E.R. 1914. The Personality of Towns No. 3: Amlwch. A Town of Yesterday. The Welsh Outlook, 1, 4, 172-173.

-

Westhead, S.J. 1991. Prospects at Parys Mountain. Geology Today, 7: 130-133. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.1991.tb00781.x